Inside the Bunkers: Remembering Wounded Knee

By Brenda NorrellCensored News

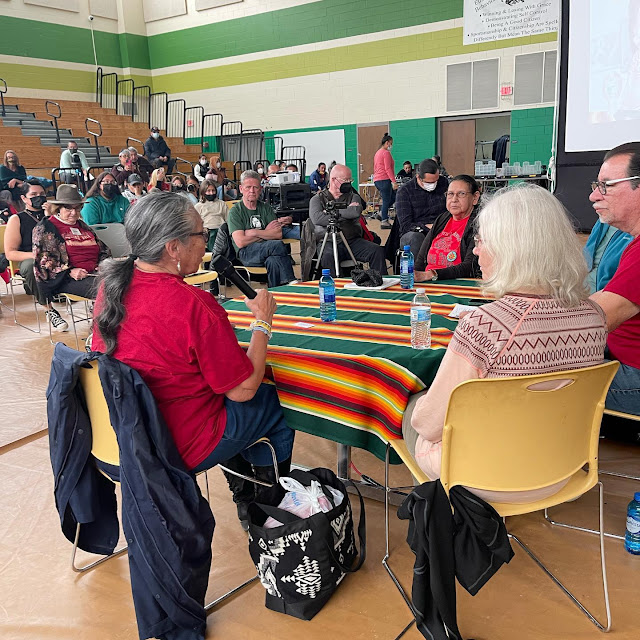

PORCUPINE, Oglala Lakota Nation -- Warrior women of Wounded Knee joined a reporter and an attorney to remember the 71 days of Wounded Knee, from the bunkers to the courtroom. Bullets whizzed by their ears as they resisted the heavily armed GOONS and the U.S. militarized assault on the people.

"Wounded Knee was just a spark, today we have flames," said Madonna Thunder Heart, Lakota, during a panel discussion of the Warrior Women Project on Saturday, during the 50th Anniversary of Wounded Knee in Porcupine on Pine Ridge.

Thunder Hawk, who served in the clinic, said the occupation continued the struggle of Alcatraz and all the struggles.

"It was always the land struggle, that's who we are."

What happened at Wounded Knee became international, Thunder Hawk said, even though the media was non-native and male-dominated press on all levels.

Yes, it was the land.

"We have every right to make a stand. We make that decision."

Thunder Hawk was 33 years old.

"I was one of the old guys."

Lavetta Yeahquo, Kiowa from Oklahoma, turned 19 years old at Wounded Knee. Yeahquo remembers being young and naive. She believed her husband, a military veteran, would somehow protect her. But that was not the case when the bullets whizzed by her head.

"It was scary. I thought I was that real tough country girl."

Yeahquo said it was a great learning experience because, before that, she didn't know her ways and ceremonies. After Wounded Knee, she went home and sat down with the elders. "They told me, 'You have that Warrior Spirit in you. Your family came from warriors."

Yeahquo said her father had always told her, "Keep your name good." She realized now what it meant.

Joanna Brown was a reporter for a college radio show covering the Vietnam anti-war protests and Asian topics at the time. Then, she turned her attention to Wounded Knee.

"I was trying to get information about it so I could cover it, but after a while, it became harder and harder to get information."

So, Brown and Barbara Lou Shafer got in Brown's red Volkswagon and went out to Pine Ridge. She showed her press credentials and received a press pass from the BIA.

A few days after they got there, the government ordered all press to leave. So ABC, CBC, NBC and all the well-paid media drove away in their fancy vans.

"They would cook steaks and drink wine in them," Brown said of the national media at Wounded Knee.

Brown told her friend, "We have to be here to witness it, if there is violence, we have to be here to cover it."

Earlier, Brown had covered the struggle in Onondaga, near where she went to school, as Onandagans struggled to save their land. Brown recalled that New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller looked so less powerful than the well-dressed Onondaga in their traditional clothes. It was there, at Onondaga, that she learned what community means to Native people, and about standing up for what a person believes in.

At Wounded Knee, Brown stayed until the end.

"It was an amazing experience."

While the leaders in the national focus were the men, it was the women who were standing there at Wounded Knee.

When it was over, Brown had her notes from those days. Akwesasane Notes asked her to come and write a book. So, she spent the next twelve months in the woods in a farmhouse putting the book together.

'Voices from Wounded Knee 1973,' originally published by Akwesasne Notes in January of 1974, was re-published in honor of the 50th Anniversary of Wounded Knee, Brown said.

Attorney Fran Olsen came to Wounded Knee when the call went out for attorneys from Ramon Roubideaux, Lakota attorney. After the first week, the United States government announced it would break down the barriers and arrest everyone inside.

"The government backed down," Olsen said.

The United States government was having its own problems because Watergate was going on at the time and the U.S. players kept getting indicted.

Olsen stayed the rest of the 71 days and divided her time between Rapid City and Wounded Knee. She helped organize litigation and found useful work for volunteer lawyers who could only be there for a week.

As for the backbone of the occupation, Olsen said, "The local leaders were mostly women, and the national leaders were mostly men."

The U.S. tried to keep local women leaders in the background -- but AIM, to its credit, would not allow it.

At one point, the government tried to stop food from coming in. Claiming that food could have guns in it, the government thought the cereal 'Pops' surely meant weapons. Meanwhile, the churches in Rapid City were gathering food and wanting to send food in.

A federal judge agreed that blocking food from women and children was not right, and issued an injunction.

The legal victory was extremely important, but short-lived, as the food blockade took another turn.

"Dickie Wilson, and his crew, they called themselves GOONS, set up another roadblock. That was the thing that kept food and legal services from getting into Wounded Knee."

Still, some of those inside would climb through the fields.

Meanwhile, Olsen's car was shot at. The fact that they wanted to stop food from going in helped gain international attention for Wounded Knee.

Olsen points out that the government capitalized on Wilson and the GOON's effort to block and destroy. The U.S. used the fact that it was facilitated "by friendly Indians."

It is a long strategy of any colonial power, Olsen said.

"No food came in, but it was a legal success."

During the panel discussion, Robert Pilot, moderator of the discussion, asked Thunder Hawk about being a taskmaster at Wounded Knee and about her sense of humor there.

"We were all Indians, that's what Indians do," Thunder Hawk said.

"That's how you get through things. The rougher it gets, the funnier people are."

Thunder Hawk remembered that the younger ones would slip out with their backpacks and go to town. They would come back with bits of coveted items, like instant coffee. Thunder Hawk remembered being in the clinic, where the trading post owner lived, and boiling water and making a rare cup of instant coffee.

"It was precious."

Meanwhile, there were firefights. The flares would go up first.

"We knew the firefights were going to happen."

Flares would hit at intervals. That is when they crawled into the bunkers, which they had dug into the ground.

"Survival instincts. Surrounded by ancestors," Thunder Hawk said.

Moderator Pilot asked about the women wearing ribbon shirts, instead of ribbon skirts. Thunder Hawk said that was a different time.

"How are you going to run in a fancy ribbon skirt," Thunder Hawk said, adding that you can't charge a barricade in a ribbon skirt.

|

| Voices from Wounded Knee 1973, Akwesasne Notes |

Yeahquo described having to go to the toilet one morning, and there was a firefight.

When she opened the door, she said, "They shot at me."

Standing in a pit being dug for an outhouse, she said, "I felt the wind of the bullets."

"We were close to death."

Yeahquo described it as a demilitarized zone of war. She was in the same bunker where Frank Clearwater was murdered. Clearwater was murdered by a federal sniper and died after being shot on April 17, 1973.

"That's something I will never forget. But I never told anyone this story," Yeahquo said.

After Wounded Knee, she battled post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Attorney Olsen was asked about the impact on her life. She said Wounded Knee gave her a sense of what an attorney could be. She was trusted by the medical teams who she helped get inside.

Through the years, and different legal jobs, she realized there are a lot of thoughtless people who become attorneys. Wounded Knee showed her that a lawyer can be a decent human being.

In the years that followed Wounded Knee, Thunder Hawk joined the resistance of water protectors at Standing Rock, the battle against the Enbridge Line 3 pipeline in Minnesota, and went to Palestine to support the resistance.

Thunder Hawk said that what they had at Wounded Knee was unity.

The people came from all over the country.

"Every one of our nations was represented."

The elders said, 'We've got the world's attention, now we've got to go further."

Thunder Hawk encouraged strong elders to show up -- so the young people know that you have their backs.

She said that what she learned from AIM is that everyone is in the movement, whether you're taking care of your family or you're in school.

"You're in the movement, that's what Wounded Knee and Alcatraz did for us."

Still, everything was a fight.

"Wounded Knee was just a spark, today we have flames."

Read more

Part I: Honoring the Matriarchs of Wounded Knee, Censored News.

https://bsnorrell.blogspot.com/2023/02/honoring-1973-matriarchs-of-wounded.html

Frank Black Horse, an Italian who posed as a Native American, was at Wounded Knee, and was later taken into custody in Canada, during Leonard Peltier's arrest. Black Horse was also at the Jumping Bull compound in South Dakota during the FBI shootout. In Canada, sources tell Censored News, Black Horse convinced Peltier to go to the Small Boy Camp, where Peltier was arrested. A community member, a Canadian police liaison turned Peltier in. Black Horse was also at the fishing rights struggle in the Northwest. Black Horse vanished in Canada after Peltier was arrested. Sources said he was posing as a medicine man in Ontario about 15 years ago.

Peltier's defense attorney Michael Kuzma has also claimed that Blackhorse was an FBI operative sent to infiltrate the ranks of AIM win the trust of its members.[20] According to Kuzma, "The FBI set the wheels in motion that got its agents killed," which he believes happened when informants working on behalf of the agency infiltrated AIM (including Blackhorse), with Kuzma citing a previously obtained document, dated 15 January 1976, in which Deputy Director General (Ops) M. S. Sexsmith of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police wrote to a colleague about Blackhorse's surreptitious provision of information from within the American Indian Movement."

The Italian Informant

Lavetta Leahyou said in an interview about Wounded Knee that an Italian, posed as an Indian using the name Frank Blackhorse, was a government informant inside Wounded Knee, and helped the U.S. indict Leonard Peltier. She said Blackhorse "Dyed his hair coal black and wore it just like one of us. And picked up an accent." Read the article: https://medium.com/whyareyoumarching/lavetta-part-2-f44827f20f9e#.rjp1l93l2 Photo of Blackhorse: https://freeleonard.org/blackhorse/index.html

Voices from Wounded Knee 1973: Those who gave their lives

|

'Voices from Wounded Knee 1973,' Akwesasne Notes, 1974 'Dedicated to Frank Clearwater, Buddy Lamont, Pedro Bissonette and all the others who gave their lives in the struggle.' |

1 comment:

In the wake of Lee Brown and Alcatraz, in the midst of an unpopular war in Viet Nam, the resistance at Wounded Knee resonated with the many in settler communities. Even if by way of the mainstream corporate media of the day. As a young man, I recall how friends and coworkers in New York City were troubled by the ongoing standoff, by the government's militaristic response which at best seemed absurd and at worst threatened violence and bloodshed. Nothing new, of course, for First Nations peoples, but a powerful spark of enlightenment for all who live on Great Turtle Island and cared enough to take it to heart.

That said, thanks for featuring the recollections of warrior women who contributed to the Wounded Knee resistance in 1973.

Also, for the companion post “Voices of Wounded Knee 1973”.

Post a Comment